—London, December 13th, 1837

The first day of Christmas

“I have a debt to pay.”

I untied my scarf, unbuttoned my winter coat and quietly voiced my request without letting the anger at my present financial troubles boil over in the presence of my editing partner, Jacob Marley, or any of the typesetters and inkers in the printing office of Bentley Publishing House, home of the weekly London Dispatch. Marley would consider shameful the pecuniary details of so much lavish entertaining. Months of parties for London’s privileged did not fall within his monetary rules governing wise social investment feted as my guests were with Cornish lamb, Liverpool hams, London roasted chestnuts, imported French wines, fancy biscuits, coach and driver, riverboat dancing on the Thames, perfumes for the ladies, and hats for the gentlemen. It was an imprudent debt without the guarantee of a shilling in return.

I said, “I’ve come up short.”

“And a Merry Christmas to you as well, Charles.” Marley raised an eyebrow of certain disdain over my social expenses and my disregard for his holiday cheer.

“I’ll have none of your nonsense this winter morning. Entertaining is good for business. They buy what we print.”

“For two shillings? That’s hardly a sound investment.”

“What am I to do? I have no means to cover this encumbrance.”

“You’re a serialist at this newspaper. An editor in this house, no less.” Marley lowered his pen and stepped away from his writing table. “You have what? Three novels to your credit and—

“Two, Jacob. Oliver Twist didn’t do nearly as well as Pickwick Papers.”

“Balderdash. They were both a smashing success. Neither has gone out of print and I doubt they ever will, sir. Have you nothing to show for it?”

I shook my head, unable to bear the sound of my own voice attesting to such folly. What had I done? I leaned in closer. “My creditors have turned the debt over. Will you have me end up like my father?”

John Dickens, my father, a well-paid clerk in the Navy Pay Office disposed to entertaining nobles and elites well beyond his means, was jailed at Marshalsea Debtors Prison with my mother and seven siblings while I at twelve years was removed from private studies at William Giles School in Chatham and sent to labor for my family’s freedom at Blacking Warehouse on old Hungerford Stairs. It was a crazy, tumble-down old house abutting the river. Its wainscoted rooms, rotten floors, broken-down staircase, the dirt and decay of the place, and the old gray rats swarming down in the cellars, and the sound of their squeaking and scuffling coming up the stairs at all times, rise up visibly before me, as if I were there again. My work was to cover the pots of paste-blacking shoe polish and tie them round with a string.

“Ball and chain, Charles.”

What an odd thing for Marley to say. “They don’t use those anymore.”

“Each iron link welded on the counting tables of greed.” Jacob circled round me, like a ghost at haunting. He grinned. He said, “Lashed to the borrower’s ankle.”

“You mock my monetary pain with far too much glee, sir.”

“The burden of your deeds you carry about like a ball and chain with only the fragile hope of salvation laid upon the mercies of a merciless creditor who—

“Thank you fondly for your fiscal cheer.”

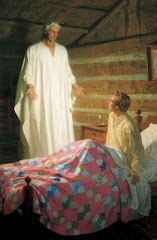

I closed the door to the front office, shutting out the pungent smell of ink from the press and the thought of Blacking Warehouse of former years. The memory of childhood should be a pleasant recollection, devoid of the past ghosts of my father’s debts, the present spirit of Jacob Marley circling about me, and the future phantom of my own recklessness certain to visit my due upon me, all of which rise up to haunt my soul like the present smell of printers ink and the memory of paste-blacking.

I said, “I need an advance. I’m good for the balance. Nicholas Nickleby is scheduled for typesetting first thing after Christmas.”

“When have we ever…?”

“Never. But I had hoped you would consider it."

“Write me some hope. I’ll see that it’s printed in the midweek run of the Dispatch before Christmas and you’ll have your advance.”

“Who reads of Christmas spirit any longer? The traditions are dying out. It’s a lamentable waning, but trust me, sir, it will not sell. I know a good story.”

“You’re a Scrooge, Charles.”

Scrooge? What a strange name to call a friend.

“Come now, tell me you haven’t wondered at the accountant who works in the third floor counting room,” Marley said in answer to my quizzical stare. “The man pinches every shilling. One piece of coal for the fire every third hour, no matter how cold. He hasn’t time to comment on the weather or bid any good day. He’s far too busy counting money.”

“So it is with the whole of London. There is something of Scrooge in each of us these days.”

I reminded Marley of the poet Thomas Hood’s commentary in the Sunday Times this week past, wherein the renowned poet argued that Christmas, with its ancient and hospitable customs, its social and charitable observances, were all in decay.

Marley said, “You see only what you want to see, Charles.”

He went off, bemoaning my predisposition to indifference and reciting his reading of the Times, quoting the famous poet who, Sunday last, rightly so had asked, if all London had forgotten the babe born at Bethlehem who had borne our grief and carried our sorrow. Was there no interest among Londoners in honoring the birth of Him who was bruised for our iniquities? Had noble and commoner alike forgotten we were healed with His stripes? Was there no hope for redeeming the winter holiday?

Marley said, “There is hope.”

“Humbug, Marley. The poet said nothing less than that Christmas is in decay. HIs words underscore the inevitable loss of a venerable tradition.”

"Peace is hardly a tradition." Marley didn't offer a further word of retort beyond his quiet comment and in the awkward, seemingly defeated silence, and me far too willing to jump on the moment and drive my point home, "There is no peace on earth," I said. "For hate is strong and mocks the song, of peace on earth good will toward men."

"That is the nightmare within the Christmas carol." Marley voiced his reply in ghostly quiet words. “As nightmarish as was your Christmas passed at Blacking Warehouse down by the river.”

“Please, Marley. Must you dredge that up?” I laid my coat over my arm, fitted myself into the angle of Marley’s writing chair, and set my boots upon the hardwood table top, which, on a twist of irony, were in terrible need of blacking-paste and a good going over with a polishing cloth. “It is a most horrible ghost story of a past I am loathe to recall.”

“You escaped your nightmare.”

“Only for the kindness of an aunt who with an inheritance reached out from a silent grave and paid my father’s debt, redeemed us from our terrible state, and won for me release from that dreadful place. And I beg of you, as a friend these many years, to never take my mind back there.”

“I would wager that the poet Hood's words are not the first time you've been transported back, Charles.”

“He penned not a word of shoe polish.”

“Blacking paste or no blacking paste, at least in Hood there is one author in London who hopes to save the waning holiday before we celebrate our last.”

“You can’t save society from itself, Jacob. If they are done with Christmas, then they are done with it. Only an act of God could divert the Thames from running its natural course.”

"The act of God is already done." Marley found a well-worn copy of the Holy Bible on his reading shelf. “The debt is paid, my good debtor friend.” He leafed through to Isaiah the fifty-second chapter, third verse where the ancient penned that we have sold ourselves for naught and yet we shall be redeemed without money.

Marley said, “Write me a story of Christmas hope without keenness for money and you’ll have your miracle of Christmas spirit for yourself and for the whole of London.”

I leaned back in Marley’s chair. There was a story in this debt of mine that brought me to Marley’s office this morning and to my senses. And there was a story in the debt my aunt paid those many years ago, doing for my father and my family what we could not do for ourselves, redeeming me from the hell of Blacking Warehouse. Are not we all debtors? Is it not the Christmas spirit that honors the birth of Him who paid our debt?

Still I said, “Marley, a story of hope is hardly good business in this, the dawning day of the cynic.”

Marley placed a counseling hand on my shoulder. He said, “Mankind should be our business.”

I thought to leave Marley to his work, but he unrelentingly followed me in silence past the press, round the stacks of typesetting bits and hammers, through the anteroom and to the front doors of Bentley House. I said, “Could you be so good as to hold the Dispatch until Christmas Eve?”

Marley opened the door and wished me well, but in a manner all but lacking of his usual Christmas cheer. He said, "What reason have we to hold the press twelve days?”

“A ghost story.” I winked and laughed a merry laugh, then tied my scarf and buttoned my coat. And before heading out into the wintry London snow I said, “A Christmas ghost story.”

Copyright December 2008 ©. Thou shalt not copy, paste, or digitally transmit this story for any purpose without the express written permission of the author.

________________________________________________

Historical Notes

Prior to writing A Christmas Carol, which was originally titled A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being a Ghost Story of Christmas, Charles Dickens was saddled with debt. Despite his successful publication and subsequent sale of Oliver Twist and Pickwick Papers as well as many well-received serialized stories in London newspapers under the pen name Boz for which he was renowned for endless cliffhangers, he was unable to pay the debt. It was under these indebted circumstances, with the traditions of Christmas waning terribly, that Charles Dickens set out to write his first of many Christmas tales.

When Charles Dickens was twelve years old his father was arrested and imprisoned at Marshalsea Debtors Prison. His wife, Elizabeth, and seven children joined him in prison. Charles was removed from private school at William Giles at Chatham and sent to work to pay off the debt at Blacking Warehouse on old Hungerford Stair overlooking the river. Of his time at Blacking Warehouse Dickens wrote:

The blacking-warehouse was the last house on the left-hand side of the way, at old Hungerford Stairs. It was a crazy, tumble-down old house, abutting of course on the river, and literally overrun with rats. The counting-house was on the first floor, looking over the coal-barges and the river. There was a recess in it, in which I was to sit and work. My work was to cover the pots of paste-blacking; first with a piece of oil-paper, and then with a piece of blue paper; to tie them round with a string; and then to clip the paper close and neat, all round, until it looked as smart as a pot of ointment from an apothecary's shop.

The poet Thomas Hood, after reading Dicken’s work, A Christmas Carol in Prose, wrote: “If Christmas, with its ancient and hospitable customs, its social and charitable observances, were in danger of decay, this is the book that would give them a new lease.”

Author's Note: This short story is dedicated to my family and friends who have shared with me, in abundant measure, the spirit of Christmas. May you each enjoy a Merry Christmas and may the Spirit of the season remain with you throughout the year.

__________________________

Join author David G. Woolley at his Promised Land Website.

4 comments:

Wonderful.

Dave, told ya! :)

Merry Christmas, David.

Thank you for leaving the suggestion of how to end "A Suit for Christmas" on LDSpublisher. Duh! Of course it should have ended that he wanted the suit for someone else and they end up giving the gifts anonymously. Then the inactive teacher finally comes to church to see the little boy who received it. So much better. THANK YOU! The idea was almost good. You're brilliant.

Post a Comment