*Editor's Note: This post is part of a weekly series titled the Promised Land where author David G. Woolley sheds his bloggish sensibilities and delves into the research and inspiration behind the characters and story lines of his Book of Mormon Promised Land Historical Fiction Series. This week find out how pottery points to Christ's visit to ancient Nephites at Bountiful.

Clay pots. They were the paper and plastic of the ancient market place. The cupboard of the ancient pantry. The distillery of the ancient winery. The cargo vessel of the ancient trade route. Versatile. Durable. Disposable. If a potter introduced an innovative design it was the beginning of a pottery rush. He had to produce the new pot in mass before others churned out copy cats. There were no intellectual property laws in the ancient Nephite world. No copy right lawyers. There was nothing to protect a potter's invention. They digged their clay, mixed it, formed it, and fired it while demand was high.

Tall pots. Round pots. Painted pots. Engraved pots. Long handles. Stubby handles. No handles. With lids. Without lids. Pouring vessels. Storage vessels. Oil, water and wine vessels. There were even artistic variations for those who could afford a little more than simple common man terra cotta. Kings embalzoned pots with their new royal name and the date of their coronation. The upper class got matching rose petals etched into the sides of their pot collections or an alligator lurking along the base. For the right price you could even have your portrait on a pot, vested in tribal warrior attire, a ring in your nose, a spear in one hand, and a peacock feather in your hair. All that painted onto a pot to hold your most prized possessions---a jade necklace, a jaguar tooth, and maybe a few obsidian blades.

The prevalence of pottery in the archaeological record makes clay pots an ideal artifact for uncovering the ancient past. Its all about distribution. When you throw a rock into a pond, the ripple farthest from the center is likely the first one formed. So it is with pottery. Say you plot on a map where each pot is found. The ones created first are likely those distributed farthest from the central point of origin. They're the ones that traveled to reach the outer most geographic borders of a civilization. (For more about the archeology of pottery you can read a previous Top of the Morning post titled Unlock the Past, Unlock your Soul)

The refuse dump of the ancient world was littered with broken pottery. Ancient home makers went through pots like their modern cohorts go through disposable zip lock bags. It was the environmental concern of millenia past. Archaeologists call the broken pieces potsherds and Nephites, like their brothers in the Old World, recycled everything including broken pottery. Cement filler. Road construction. Mortar. And the most intriguing recycled use for broken pots? At least for the anthropologists and archaeologists it was as a writing medium. Potsherds were the sticky notes and letter head of ancient peoples and if they were used for writing scholars called them ostraca. This excerpt from the epilogue of Power of Deliverance dramatizes the importance of ostraca to researchers searching for the Lakhish letters---broken pottery used for military correspondence written in Lehi's day near Jerusalem.

John was dressed in khaki, pleated pants, a tan shirt and a wide-brimmed African hunting hat his wife gave him the day the expedition sailed from Dover. This was no safari and John was no hunter, but Mrs. Starkey believed anywhere her husband went in search of the ancient past was a jungle, and the hat did have power to shield him from the intense Palestinian sun. Even in winter, its rays had a dizzying effect on the mind after hours in the trenches. The hat cast a shadow over his round cheeks and thin English nose he inherited from his great-grandmother, the Duchess of Yorkshire. If only he’d inherited one-tenth of her estate, he’d have more than enough to continue this dig until he found the evidence he sought. It had to be here, somewhere amid these ruins, and he had two years left to find it—the sponsors had signed on for twenty-four additional months and not a fortnight more.

John turned back to the tent, undid his top button to keep the heat from raising a sweat on his brown, chewed on the end of a horned pipe and read the sign over the door. It was a ritual he observed each day after tea, if it were possible to call it tea. The sign posted over his tent door read: The Wellcome Archaeological Research Expedition to the Near East at Tel ed Duweir—Tel for mound of buried ancient ruins and Duweir for some Dutch explorer of the sixteenth century who had nothing to do with the real significance of this hilltop. This was the ancient site of Fort Lakhish and John L. Starkey was going to prove it to the world. Or at least to his colleagues back at the London Museum of Antiquities. They were sure to appropriate more funding if he could come up with solid evidence from beneath the rubble of centuries, certifying that Tel ed Duweir was the legendary Fort Lakhish.

In the ancient world a potter was vital to the the local economy. Wealthy. Respected. A leader. But despite the potter's station in society they had no idea their work would become prized artifacts sought by modern archaeologists. So prized, in fact, that not creating at least one major character to assume the role of a potter in the Promised Land Series would be an oversight of Titanic proportion. Enter Josiah the Potter and his daughter Rebekah in this excerpt from Pillar of Fire.

Aaron limped past the stone masonry before stopping at the corner to rest on his cane and, as always, study the entrance to the property of Josiah the potter. He always checked the potter’s gate to see if his daughter, Rebekah, stood between the posts, but all he could see was thick black smoke billowing from the kiln chimney. It swirled over the high brick wall surrounding the firing yard, before blowing into the street and filling his eyes with enough bite to force them closed.

Aaron rubbed the smoke from his eyes and checked the gate again. There was no one selling pottery—-"no one” meaning no Rebekah. He could cross the street without risking her seeing him with a cane. He was halfway over when a sharp tingling shot through his feet. Not enough to stop him, but when he reached the other side, the full force of the hurt struck like lightning. The skin on the underside of his feet began to tear. A little at first, then a sharp splitting across the arch. It was a tearing he knew too well. He bent at the waist, bowing his cane to near breaking before falling to his knees like a man in prayer, begging not for relief but for privacy. He’d endured this kind of pain for months in the solitude of home, but never in public. He clutched the nearest cobblestones and let the warm blood ooze between his toes. The pain passed quickly if he held still and let the blood dry.

Another cloud of smoke blew down from the potter’s chimney, thick enough to choke him to tears. He wiped his cheeks and, when the smoke cleared, found himself staring at a dreadfully beautiful sight that stood at the far end of the potter’s wall in front of the gate to the firing yard. Josiah’s daughter toiled in the shifting smoke, arranging pottery on the canopied selling tables. Thank heavens she hadn’t seen him kneeling there. She disappeared inside the gate and returned with a stack of cups. It was like watching an angel do the work of humans. She dressed in a white robe, and had saintly black hair, a cherubic smile and deep jade eyes. But this wasn’t heaven, it was Jerusalem. And there could be no curse more damning than to be seen as less than whole. What woman would have a crippled suitor?

The pain lessened and he stood and spread his weight from heel to toe. His stirring caught Rebekah’s attention. She set down the cups and blinked, clearing her lashes of the ash that settled out of the smoke.

“Good morning.” Rebekah nodded.

Aaron stayed downwind and shouted through the smoke. “Fine pottery you have there.”

“I’m sorry.” Rebekah leaned over the selling tables. “I didn’t hear you clearly.” Her apology echoed off the store fronts like music from a piper’s flute. “What was that, sir?”

Sir? No one had ever called him that before.

“Beautiful pots,” Aaron said.

“They’re cups.” Rebekah raised one through the smoke, glazed to a brilliant polish. “But we do sell pots. Would you like to see one? I have a stack inside the yard. Why don’t you come over and I’ll show you in. You can get a good look at the—”

“I can see fine from here.”

“They’re behind the walls.” She motioned to the gate.

“I’ve heard about them.”

“From Papa, no doubt. He’s proud of his pots. He’s proud of everything he’s created around here.”

“I don’t blame him.” Aaron admired her long black curls and high red cheeks until it wasn’t proper to stare, and then he stared some more. “He has every right to be proud.”

Rebekah cupped her hand to her ear. “Pardon me?”

“I was saying that your father—”

“Oh, he’s gone for the morning. He has council meetings the first of every week.”

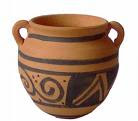

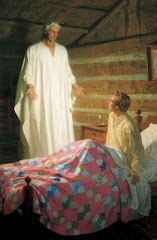

The process of digging clay from the earth and molding it into a useful, artistic pot was a powerful metaphor in the ancient world. Isaiah wrote of God as the potter and man as the work of His hands. Richly decorated incense bowls, figurines and other religious symbols were fashioned of clay. Around the time of Christ's appearance to the Nephites, the peoples of ancient Mesoamerica discarded their clay religious artifacts along with their many different religious practices and adopted a single common religious belief. Archeologists have yet to explain this sudden unified change. It seems some catastrphic event may have triggered the unexplainable religious change. Use of a clay religious drinking bowl spread across the whole of Mesoamerica. LDS scholars suggest it may have been used for centuries, beginning around 35 A.D. as part of the sacrament instituted by Christ when he appeared to the Nephites. It was a simple drinking bowls wihtout any adornments, etchings or paintings. The origin of distribution for what may have been ancient Christian sacramental drinking bowls points to here. Coatzacoalcos.

View Larger Map

Most LDS scholars agree that this gulf coast area on the north/east side of the narrow neck of land known as the Isthmus of Tehuantepec is the location of the Nephite Land of Bountiful. Pull back in the interactive map about five clicks and you'll see the narrow neck isthmus. You'll also see the likely Land of Zarahemla located to the south east near Tuxtla Gutierrez in the Chiapas Central Depression (for more about ancient Nephite geography read the Top of the Morning post titled Borders). The ancient religion established by the God Quetzalcoatl sometime between 30 and 50 A.D. also appears to originate from the same location as did these ancient religious drinking bowls.

In this final excerpt from Day of Remembrance, Nephi uses Isaiah's potter & clay metaphor to ease the concerns of his brother Sam.

River water seeped into the clay pit and pooled around Sam’s ankles. It was a curse that the finest clay stood at the mouth of the canyon. Cool air streamed through two miles of sheer granite walls from the Fountain of the Red Sea and chilled his mud-soaked body. He went to his knees and dug an armful of clay. How did he ever let himself fall this far? He was caravan master of Jerusalem’s finest camel herd not a clay digger. They should be trafficking in gold, or silver, or olive oil—anything but mud. Sam pealed a layer of red earth off his fingers. Mucking through clay was nothing like reading maps and plotting a course across the deserts of Sinai. He was neither a clay digger nor a potter, but in this forsaken valley there was nothing to trade. All of Sam’s training—the years he studied in the map room, apprenticed in the animal corrals and drove the camel herd over the trade routes to Egypt—was wasted unless he returned home where his skills and business sense were sure to win him a comfortable life.

He wrapped his arms around himself to warm him against the chilling breeze. “We never should have come here.” His body began to tremble. “Father’s a dreamer and he led us to the land of his dreams to die.”

Nephi said, “He’d never do that to us.”

“You best get used to this place, son.” Hagoth pulled himself out of the pit. “Otherwise your father’s dreams will become your nightmare.”

“Papa.” Moriah waved his hand at the boat builder. “Let him alone.”

Sam said, “How do you know Lehi isn’t gone mad?”

Nephi said, “You’ve been listening to Laman again.”

“I hear what Father says. He doesn’t know where we’re going from here.”

“See this.” Nephi opened his hand and held out a ball of red mud. “The prophet Isaiah wrote that we’re all clay and God is the potter and we’re the work of His hands.”

“Isaiah didn’t know of this madness.”

“Lehi’s our father. He’s the potter and we’re the clay and a good potter would never lead the work of his hand into this wilderness to die. Lehi brought us here to save us.”

Sam said, “Do you really believe that?”

“I prayed to know if I could trust father.” Nephi pressed the clay into Sam’s hand. “The Lord softened my heart.”

Sam slowly raised his gaze from staring at the clump of clay.

Nephi said, “We were led here by God.”

“How can you be so sure?”

“I was visited by the Holy Spirit.” Nephi leaned closer. “Heaven is watching over us.”

There was no reason Sam should listen to his younger brother—this boy with dark curly hair gone red with a covering of mud. Wasn’t Nephi the same boy who believed Sam when he told him he could climb the olive trees of the old vineyard to get to heaven? But Nephi wasn’t a young boy any longer. Somehow, without Sam noticing, the youngest of all the brothers had become a man. He was always strong and stout beyond his years—a fine wrestler, a hard working soul, and a studious lad—but somewhere in the run of years Nephi had stored up a reservoir of wisdom that was just now beginning to spill out of him. He was the one assigned the tasks about the estate the others refused to take, the funny toddler, the long-legged awkward boy, but this morning he was nothing if not noble, covered with red clay from head to foot and standing with Sam in the middle of this cold clay pit, buoying Sam’s spirits and helping him see what he could not see on his own. For the first time in his life Sam understood that Nephi was more than mother’s youngest child. They were brothers and he couldn’t deny the power of Nephi’s words, his certainty chasing away the confused mix of anger and fear that gripped him since abandoning their inheritance at Jerusalem.

Nephi’s deep brown eyes were filled with the intensity of his words and his steady voice filled Sam with a peace he’d not known since before they left Beit Zayit. A tear burned in Sam’s eye and he quickly brushed it away. He threw the ball of clay to the ground. “I hope there’s a land as fine as the one we left behind.”

“There is, Sam. Somewhere there's a land of promise for us. God doesn’t lie.”

__________________________

Join author David G. Woolley at his Promised Land Website.

No comments:

Post a Comment